Emmanuel presented on the history of the term ‘minority’ at the workshop National Self-Determination in the 20th Century held at the University of Tartu

In the the 1920s and early 1930s, Estonia was a leader in minority protection in Europe. In 1925, the young republic adopted a law on non-territorial autonomy that, until the 1934 coup d’état, granted minority groups with at least 3,000 members the possibility to create institutions that could manage education and cultural affairs. Given this tradition, it is an ideal place to study issues concerning diversity, recognition, and individual and collective rights.

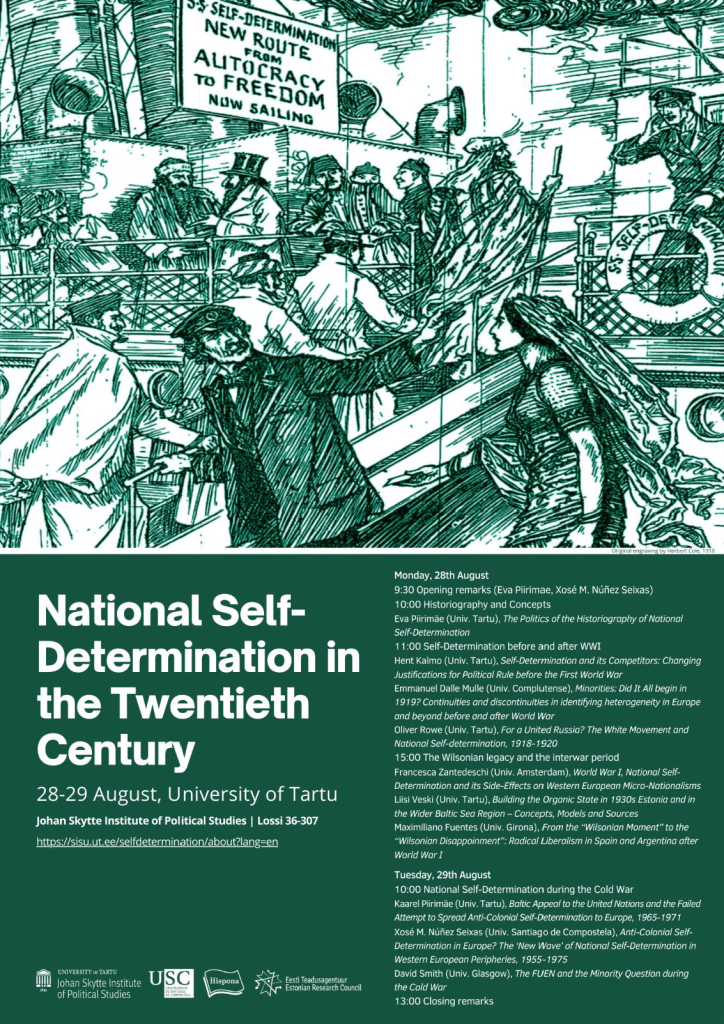

On August 28-29, researchers from all over Europe gathered at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Affairs of the University of Tartu to discuss the origins, evolution and complexities of the principle of self-determination. Emmanuel presented a paper entitled “Did it all begin in 1919? A history of the term minority as a category of practice from the 18th century to the interwar period”.

Until recently, Emmanuel argues, the history of minorities and minority rights has followed a fairly standard account. Begun in Europe with the religious wars of the 16th and 17th century, minority protection developed further in the 19th around the Eastern Question and peaked in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, with the minority treaties negotiated at Versailles (there is a second part of the story after 1939, but this does not concern us here). This account has now come under attack. Several authors affirm that until 1919 the term minority, meant as a permanent not a transient minority, was marginal, if not absent, in domestic and international discourses on diversity. Emmanuel shows that revisionist authors have too quickly dismissed the relevance of much of the 19th century for the history of minorities and minority rights. Above all, they have missed an opportunity to explore in depth alternative trajectories to the traditional central and eastern European story. Emmanuel’s paper is a first attempt to draw such an alternative itinerary. Examining a broad range of sources, from parliamentary debates on Ireland and Canada, to demographic and statistical analyses on the populations of the German and Habsburg empires, the paper tracks how philosophers, politicians, geographers and statisticians anticipated a world in which nationality conflicts would play out in the emerging grammar of minorities and majorities. It further suggests that two forces in particular drove the process: political representation, with its imperative of majority rule and the cognate question of minority rights; and census practices, which increased the legibility of the social, constructed difference and fuelled anxiety about numerical superiority and inferiority. The paper received useful feedback that will certainly help improving the final version.

The workshop covered a broad range of topics, from pre-First World War principles of political legitimacy alternative to self-determination to attempts to mobilise anti-colonial self-determination in the soviet space in the 1960s, through the rejection of self-determination by the White Movement during the Russian Civil War and the impact of the Wilsonian Moment in Argentina. In line with the core arguments of the Myth of Homogeneity project, the different contributions confirmed that self-determination, minorities, multi-ethnicity and plurinationalism are realities that extend, and have extended in the past, well beyond central and eastern Europe.

The conference was also the occasion for a visit at the Villa Ammende, in Parnu (pictured above). The house is a fine example of Art Nouveau architecture and, until 1927, the summer residence of the Ammende family. Ewald Ammende, founder of the interwar Congress of European Nationalities, spent many summers there, probably discussing about minority rights in the garden terrace. He still watches discretely the guests visiting the house from a hidden corner in one of the many dining rooms.