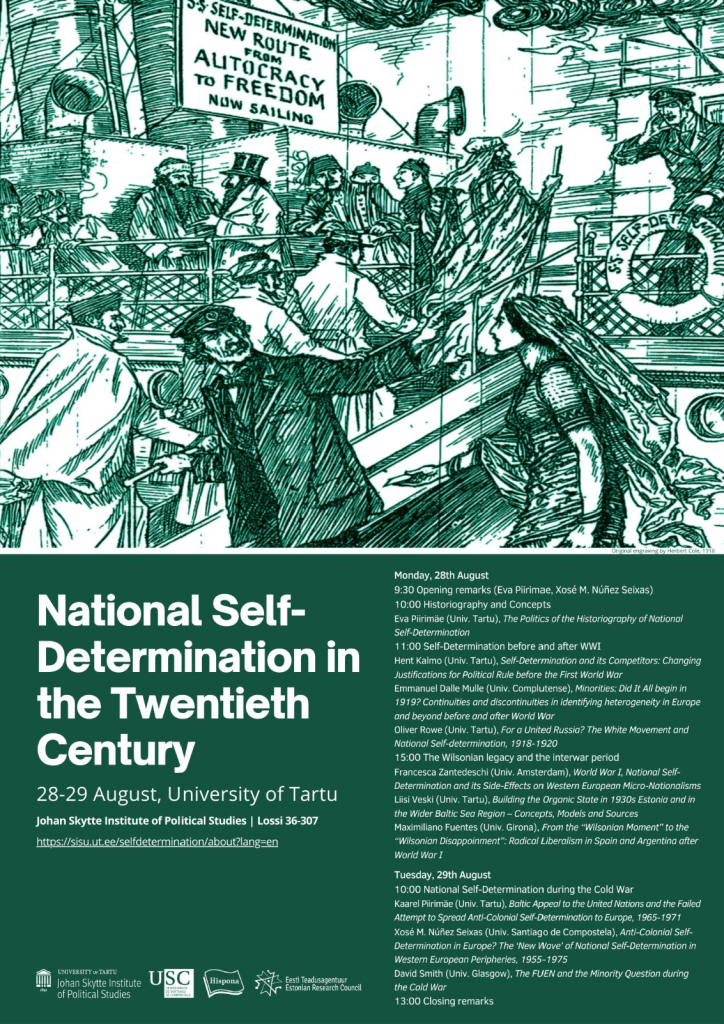

What is Flanders? This provocative question lies at the core of a new publication from the Myth of Homogeneity project just appeared in Contemporary European History. The publication argues that answering this question can move this European region from the margins of international historiographies on the inter-war period to the centre of an alternative account of minority and nationality questions after the First World War.

Scholarship on minorities in the inter-war period have largely ignored the Flemish question. One obvious reason is that the Flemish accounted for a majority of Belgium’s population. This article, however, argues that the domestic and international historiography would benefit from considering the Flemish a minority, albeit a peculiar one. It suggests that the Flemish question embodies the contradictions of an age in which the nationality question ‘morphed into the minority question’ (as Holly Case has pointed out) without disappearing altogether.

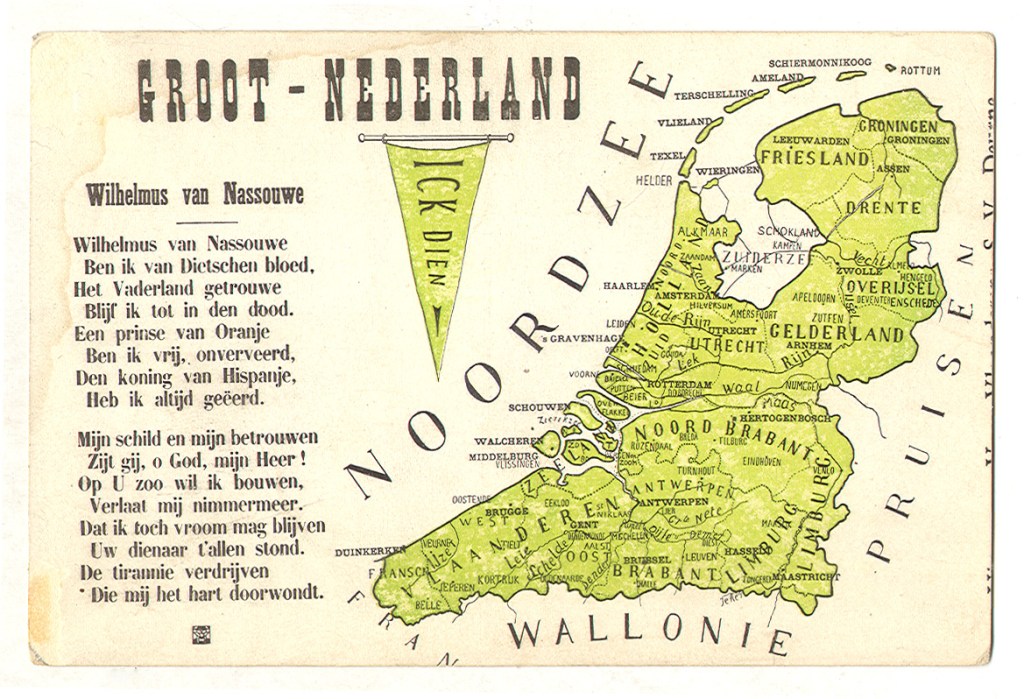

The article traces the evolution of different understandings of Flanders in the Belgo-Dutch-German transnational space. Within this context, different understandings of the Flemish population coexisted from the end of the First World War until the 1940s: as a region of Belgium with cultural ties to the Netherlands; as an oppressed nationality and a majority in Belgium that fought for linguistic protection and equality like many minority communities across Europe; as a nation endowed with a right to self-determination; as the smaller part of the Greater Netherlandic nation; as low Germans (Niederdeutsche) and thus members of the broader German Volk. Most of these understandings located Flanders at the frontier between majority and minority, and the Flemish question between a minority question of the inter-war years and a nationality question of the pre–First World War age.

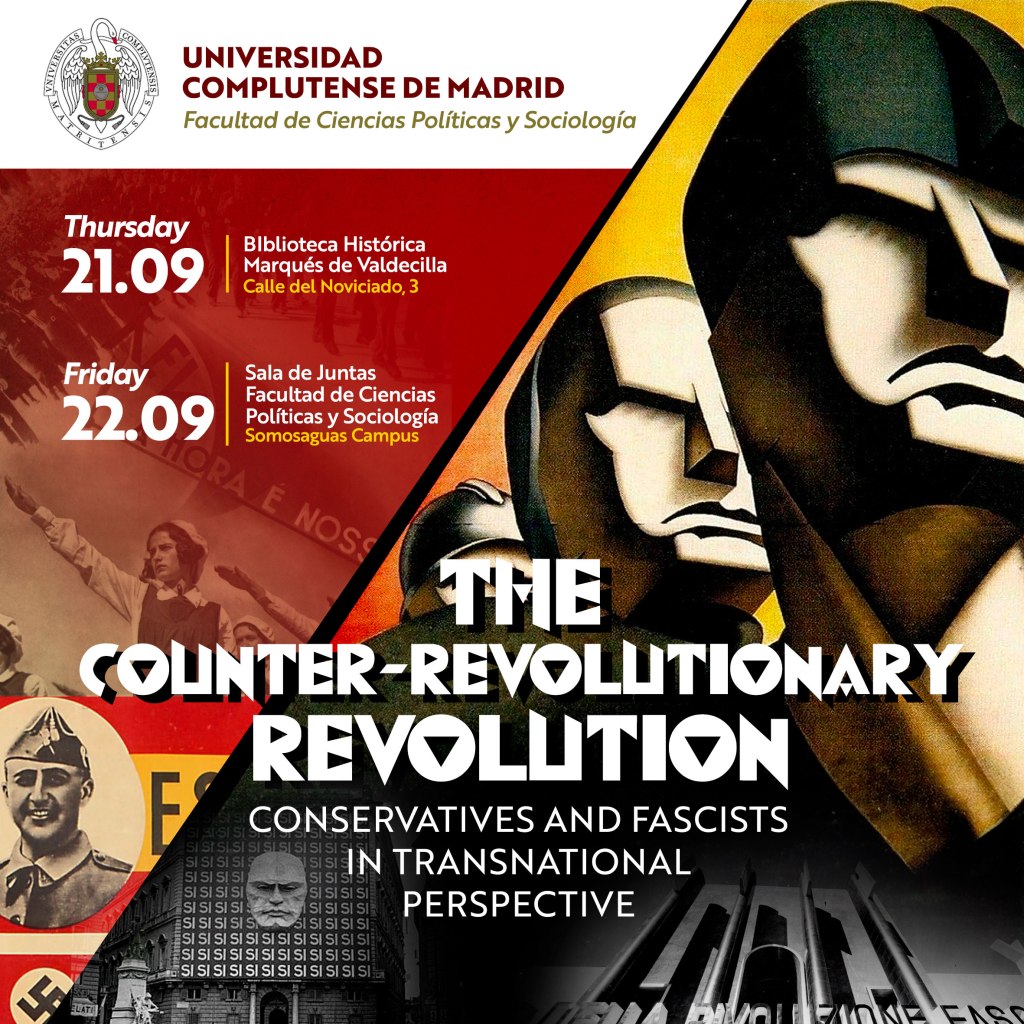

The article follows the evolution of these understandings during the inter-war period, focusing particularly on understandings that were pursued by radical Flemish nationalists and their German allies. It shows how Flemish radical nationalists criticised their moderate counterparts for making claims of linguistic equality and protection that, in other European countries, were the prerogative of minority communities. Yet, with their thought and action, Flemish radical nationalists also unwittingly steered the Flemish population into a minority position, by either defining it as part of a Greater Dutch nation, or striking an alliance with Nazi Germany that eventually threatened the existence of the Flemish population as an autonomous group altogether.

The publication finally shows how such understandings challenge traditional conceptions of minorities, majorities, nationalities and kin states. It further contributes to a broader shift in historiographies of nationalism and diversity in inter-war Europe by moving focus from East to West and considering minority questions as a pan-European phenomenon.