H-Nationalism is proud to publish here the tenth post of its “Minorities in Contemporary and Historical Perspectives” series, which looks at majority-minority relations from a multi-disciplinary and diachronic angle. Today’s contribution, by Patrick Utz (University of Edinburgh), examines the fluid identities of German-speakers in South Tyrol in the 20th and 21st century.

South Tyrol or Alto Adige is Italy’s northernmost province. Mainly populated by German-speakers, the province became part of Italy after the breakup of Austria-Hungary in 1919. Today, far-reaching autonomous competencies and a mandatory power-sharing system includes both German and Italian-speakers. This has assured the peaceful cohabitation of the province’s diverse population. But while contemporary institutions are modelled around linguistic identities, South Tyrol has always been shaped by a multitude of overlapping and frequently ambiguous allegiances. Unpacking this complexity allows for important insights beyond South Tyrol: it sheds new light on how national minorities relate to culturally akin, neighbouring countries without raising fears of historical revanchism and irredentism.

Traditionalist regionalism

When South Tyrol became part of Italy, regional identities tended to be stronger than the linguistic-nationalist divisions that surfaced later in the twentieth century. Allegiances lay with the former Habsburg Crownland of Tyrol that included German-speakers and Italian-speakers between the river Inn in the North and the Lake Garda in the South. This identity built on Catholic conservativism and the collective memory of the resistance against Napoleonic troops in this mainly agrarian region. Clearly, these tenets were at odds with the liberal ideas that inspired the Risorgimento and shaped the Italian state into which South Tyrol was incorporated.

This alienation was not exclusive to the German-speaking minority that found itself in a new nation-state. It was shared by many Italian-speaking Tyroleans in what is now the Province of Trento. Indeed, Trento’s Catholic tradition would become influential within Italy’s powerful Christian democratic movement after 1945. Additionally, in the Austrian part of Tyrol, notions of the wider multilingual region never entirely faded. North Tyrol’s main university, for instance, has continued to offer Italian-language courses and hosts a faculty of Italian law.

By the middle of the twentieth century, however, increasingly aggressive forms of nationalism on both sides of the linguistic divide superseded patterns of pre-modern, regional identification.

Nationalist excesses and their remnants

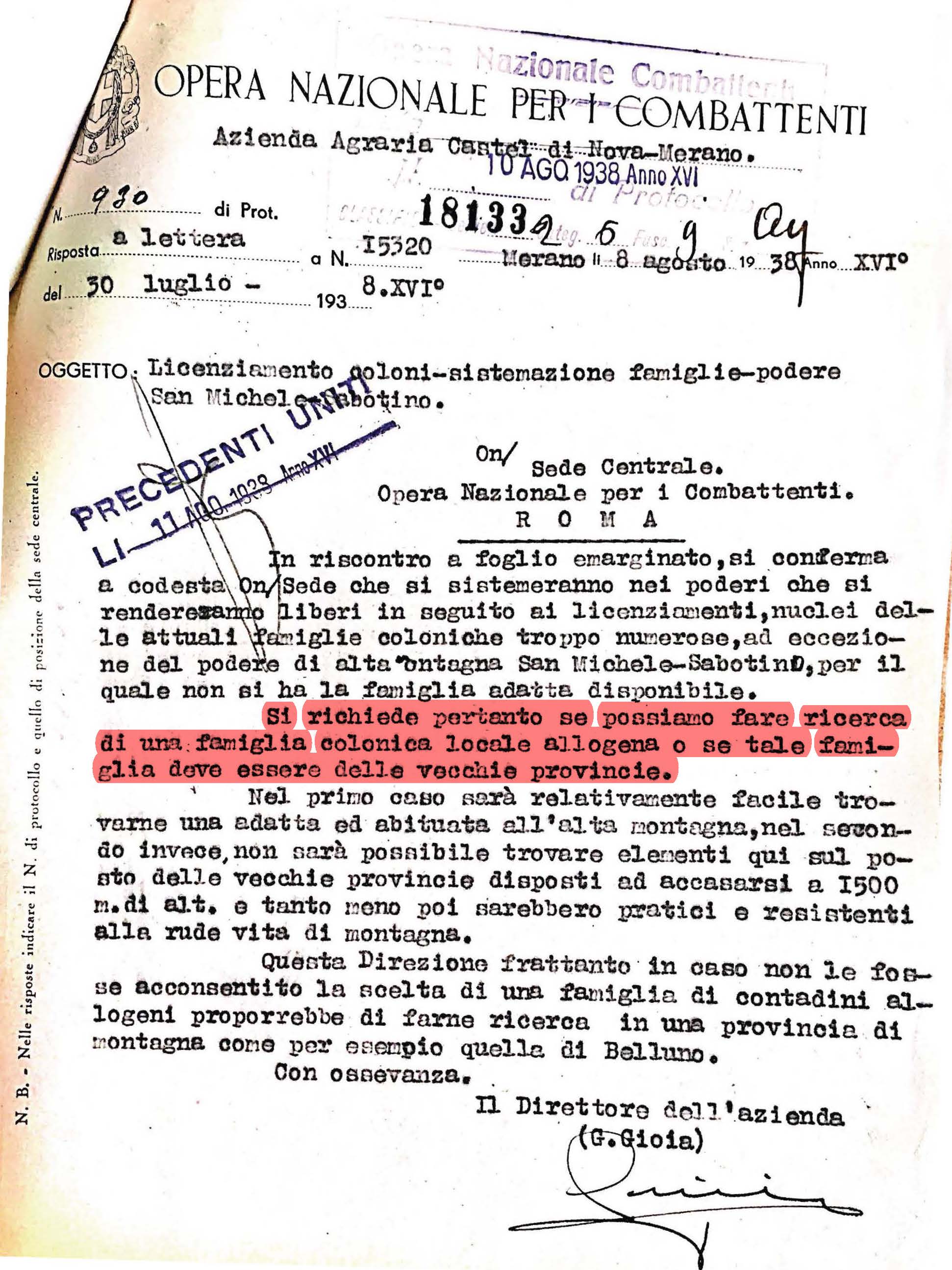

National identities based on linguistic differences had taken shape over the course of the nineteenth century but were exacerbated with the rise of Nazism in Germany and Fascism in Italy. While the Italian Fascists aimed to forcefully assimilate German-speaking South Tyroleans, many among the latter hoped for South Tyrol to be incorporated into Hitler’s Reich. As part of their political rapprochement in the 1930s, the Italian and German regimes sought to resolve the issue of South Tyrol through population resettlement. German-speakers should decide whether they wanted to stay in South Tyrol, with the prospect of being forcefully assimilated; or whether they wanted to be resettled to the Reich. The plebiscite on resettlement deeply dived Italy’s German-speaking minority. The two sides accused each other of betraying their German national heritage or their Tyrolean homeland, respectively.

Large-scale resettlement never materialized amidst the devastation of the Second World War. Yet, the plans to do so revealed the deep-seated tension between those South Tyroleans who subscribed to German nationalism; and those, who maintained a regional identity where local allegiances trumped linguistic divisions.

After the Second World War, South Tyrol’s political elites aimed to reconcile these two camps within a common political structure for the whole German-speaking minority. This led to the creation of the South Tyrolean People’s Party (Südtiroler Volkspartei, SVP) in 1945. The SVP was highly successful in bringing together the different segments of the German-speaking minority and obtained over 90 percent of German-speakers’ votes. Yet, the defining characteristics of the minority remained contested. One wing considered the German-speaking South Tyroleans to be a linguistic-cultural group within the wider region of Tyrol that was now split between Austria and Italy. The other wing emphasized South Tyroleans’ membership within a larger German nation.

None of the resulting political aspirations put forth by either wing could feasibly be pursued in South Tyrol’s post-war environment. The aggressive nationalisms had irreversibly politicized the linguistic differences in South Tyrol. Thus, multilingual regionalism was no longer an option. At the same time, Western Europe’s emerging security structure solidified state borders and discredited all forms of pan-Germanism, which precluded the option of secession.

Re-interpreting regionalism

The SVP’s compromise was to demand autonomy for German-speakers within the Italian state, and a neat separation of South Tyrol’s language groups in public institutions. The reinstated Republic of Austria and the Austrian Tyrol were crucial in supporting this cause, despite Austria’s eagerness to differentiate itself from its own infamous German nationalist heritage.

The SVP and Austria’s negotiations with the Italian government succeeded in 1969. Since then, robust mechanisms for territorial autonomy and minority self-government have gradually been put in place. The autonomous institutions have substantially contributed to South Tyrol’s political stability and economic success. This has turned the institutions themselves into a reference point for collective identification. In 2014, more than 80 percent of German-speakers in the province identified as “South Tyroleans”. Allegiances with pan-Germanic and wider Tyrolean identities have markedly weakened.

At the same time, new forms of regionalism are allowing for a patchwork of identities that straddle linguistic and political borders. Oftentimes the resulting identities combine reinterpretations of historic elements with newly emerging allegiances. The SVP, for example, has become more vocal in portraying Austria as South Tyrol’s “motherland”. This stands in sharp contrast to the party’s previous commitments to the broader German cultural heritage. Simultaneously, the party promotes a “European Region of Tyrol” as part of the European Union’s cross-border initiatives. This embryonic entity resembles the historic Crownland of Tyrol and includes Italian and Germanic-dominated regions. Voters, too, have shown appetite for more political diversity. Votes still tend to be overwhelmingly cast to candidates from one’s own linguistic group. Yet, the once hegemonic conservative SVP now is in fierce competition with liberals, Greens and the populist right; with each challenger presenting their own vision of a South Tyrolean identity.

Conclusion

South Tyrol’s autonomous institutions may correctly be commended as “one of the most successful cases of consociational conflict regulation in the world”. The reasons for their success lie as much in their institutional design as they do in the complex and multi-layered identities of the province’s population. The nationalist excesses of the twentieth century have essentialized individual traits of these identities (in this case, language). However, the recognition of multiple, simultaneously held allegiances can dilute national antagonisms. The future success of South Tyrol’s institutions and of those with the aim to replicate its model depends on giving voice to this diversity.

Sources

Alber, Elisabeth, and Carolin Zwilling. “Continuity and Change in South Tyrol’s Ethnic Governance.” In Autonomy Arrangements around the World: A Collection of Well and Lesser Known Cases, edited by Levente Salat, Sergiu Constantin, Alexander Osipov and István Gergő Székely, 33-66. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităţilor Naţionale, 2014.

Carlà, Andrea. “Peace in South Tyrol and the Limits of Consociationalism.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 24, no. 3 (2018): 251-75.

Grote, Georg. The South Tyrol Question, 1866–2010: From National Rage to Regional State. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2012.

Pallaver, Günther. “The Südtiroler Volkspartei: Success through Conflict, Failure through Consensus.” In Regionalist Parties in Western Europe: Dimensions of Success, edited by Oscar Mazzoleni and Sean Mueller, 107-34. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Steurer, Leopold. “Südtirol 1918-1945.” In Handbuch Zu Neueren Geschichte Tirols. Band 2: Zeitgeschichte. 1. Teil: Politische Geschichte, 179-312. Innsbruck: Universitätsverlag Wagner, 1993.

Patrick Utz is a PhD candidate in Politics at the University of Edinburgh. His research focusses on minority nationalism, irredentism and kin-state politics. It has been published in Nationalism and Ethnic Politics.

The Minorities in Contemporary and Historical Perspective series is organized by the Myth of Homogeneity Research Project at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, and the Centre on Constitutional Change at the University of Edinburgh.

For more information, please visit:

The Minorities in Contemporary and Historical Perspective series is organized by the Myth of Homogeneity Research Project at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, and the Centre on Constitutional Change at the University of Edinburgh.

For more information, please visit: