The MoH team co-organised a conference at the Complutense University of Madrid

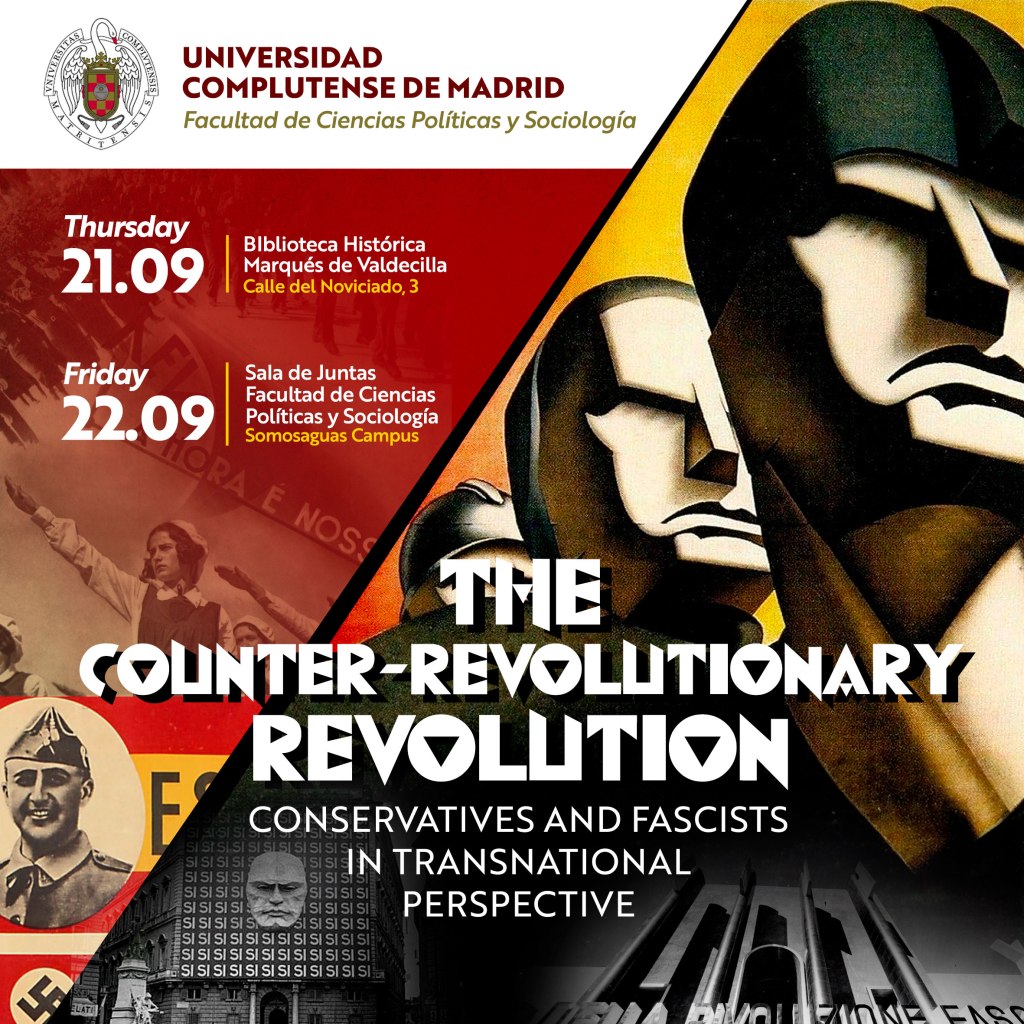

After trade flows, social policy and the environment, the transnational turn has recently impacted the study of conservatism and fascism as well. The MoH team decided to contribute to this trend organising an international conference entitled ‘The Counter-Revolutionary Revolution: Conservatives and Fascists in Transnational Perspective’, which took place on 21-22 September 2023 at the Complutense University of Madrid (co-organised with José Miguel Hernandez Barral, Alejandro Quiroga, Javier Muñoz Soro and Daniele Serapiglia).

In the last few years, the transnational approach has opened up new perspectives for research on the circulation of elements of the ideologies and practices of counter-revolutionary and fascist movements and regimes in inter-war Europe. The transnational approach has also emphasised the initially European and, later, global character of fascism and the counter-revolutionary Right as a response to the crisis of liberalism after the First World War. The conference thus aimed to contribute to the study of fascism and the counter-revolutionary Right as transnational phenomena by focusing on the appeal, external projection and reception of fascist and authoritarian regimes, ideologies and practices in Europe and beyond. Contributions ranged from the March on Rome as a transnational event, the reception of fascism in counter-revolutionary dictatorships in Spain, Portugal and Austria, the adaptation of fascist corporatism in southern European authoritarian regimes and the transnational participation of Italian ‘volunteers’ in the Spanish Civil War.

Emmanuel presented a paper entitled Betting on the wrong horse? Reimond Tollenaere, Staf De Clercq and Nazi transnational support to Flemish radical nationalists, which examined transnational influences, collaborations and dilemmas between radical nationalists in the Flemish-Dutch-German transnational space. There, he argued that the Flemish question during the interwar period embodied the contradictions of an age in which the nationality question that had been ubiquitous in the long 19th century ‘morphed into the minority question’ without disappearing altogether. The quickly nationalising population of Flanders was a demographic majority that, in many ways, behaved as a sociological minority, thus blurring the supposedly tidy lines of division between majorities and minorities, as well as between nationality questions and minority questions.

He also showed that the transnational activities of Flemish extreme-right nationalists and German authorities challenge traditional conception of the relationship between minorities and kin-states. On the one hand, several German actors from the late 19th century onwards identified the Flemings as part of the broader German Volk (as Niederdeutsche). On the other, despite pervasive pan-Netherlandic claims within Flemish nationalist circles, Flemish radicals looked much more towards Berlin than The Hague for support in their struggle for self-determination. Above all, under the Nazi occupation, Flemish extreme-right nationalists who worked to obtain external support, discovered that they were being treated as a German minority that had to be reabsorbed within the larger body of the German Volk. They thus confronted an irresolvable dilemma between their Flemish allegiance and their fascist ideological commitments. Having bet on the wrong horse, they sacrificed their self-determination goals to realpolitik and their allegiance to extreme-right ideals. He concluded that the Flemish story shows the relative and situational nature of the categories of majority, minority and nationality, which are as much self- as hetero-attributed.