Emmanuel presented a chapter of his next monograph at the prestigious Santos Juliá history seminar in Madrid

Innovations usually come from the West. This is the stereotypical view that has been prevalent in academia and outside for a long time. Yet in one field of academic research central and eastern Europe has been a trailblazer, both as an area of empirical research and as a site of knowledge production. From the early 2000s, researchers working on the history of this region have introduced and developed the concept of national indifference, along with further iterations of this notion such as instrumental nationalism and situative ethnicity. Although contested, these works have brought about a quiet revolution in the field of nationalism studies, questioning the nationalisation of European societies at the beginning of the 20th century and, more broadly, the pervasiveness of national identity as a form of identification that would supposedly be salient in all aspects of social life and at all moments. However, few authors have tried to apply national indifference to western European contexts.

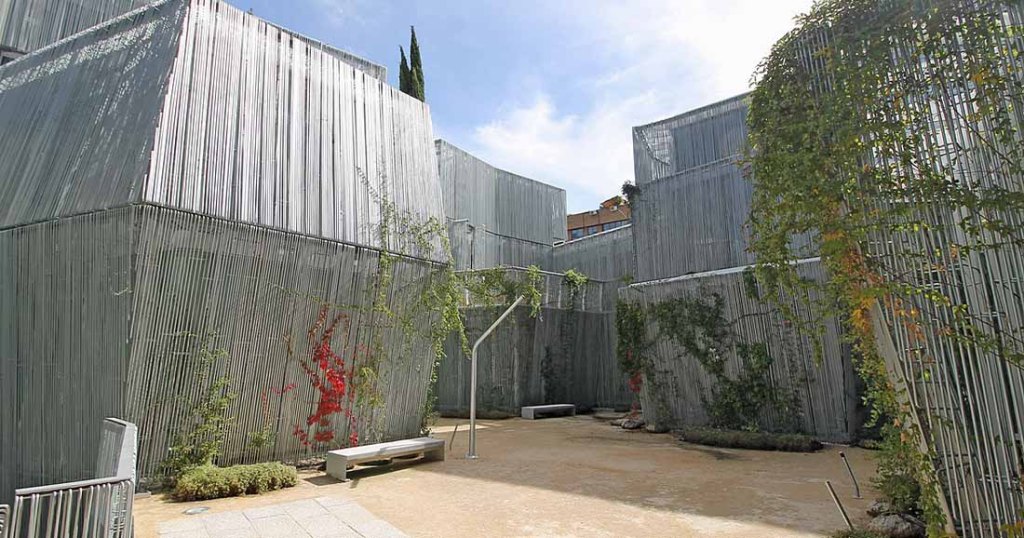

In the third chapter of his new monographs, The Myth of Homogeneity: Minority Questions in Interwar Europe, which he is completing at the Complutense University of Madrid, Emmanuel is doing precisely that with majority-minority relations in interwar Belgium, Italy and Spain. On 29 February 2024, he presented the chapter at the prestigious Santos Juliá monthly seminar held at the Fundación Giner de los Ríos in Madrid (pictured above).

The chapter rejects a dichotomic view of nationalisation and national indifference, as if one had to choose between a world where nationalism is a driving principle of political legitimacy and social organisation and one in which it is irrelevant. On the contrary, the chapter defends the idea nationalisation and national indifference coexist and feed each other. This understanding of national indifference was there all along in the works of authors such as Pieter Judson, Tara Zahra and Jeremy King, who formulated the concept, but has somehow been lost from view in later works on the subject. Then, the chapter looks at the relationship between nationalist militants and the broader population in the Basque Country, Catalonia, Flanders, Eupen-Malmedy, South Tyrol and Venezia Giulia with a focus on the Wilsonian Moment (at the beginning of the interwar period), on education policy in these minority regions in the 1920s and 1930s, and on the radicalised context of the late 1930s, especially around plebiscites and elections held in these regions during those years. The chapter shows that although minority nationalist organisations were increasingly popular in these areas they still had a hard time mobilising voters around key items of their agenda, such as demands for autonomy as well as for schools in minority language. At the same time, the chapter also suggests that, while it is true that ordinary people in minority regions took into account a number of different principles and forms of identification in their everyday life beyond national identity and beyond the injunctions of nationalist minority leaders, the radicalised climate of the late 1930s, along with the holding of different plebiscites and elections (the latter cast as plebiscites in the public debate) in a number of these regions, somehow reduced the space for indifference.

A number of commentators shared their views on the chapter and made suggestions for improvements that will be integrated in later versions of the text. As usual, the session ended with an informal gathering at a nearby restaurant in Madrid, where the participants kept exchanging comments and opinions on nationalism, national identity, indifference and contemporary history more in general.